WHAT DO YOU REMEMBER?

There’s been a big event in my household.

We bought the next instalment of the Star Wars franchise. It was a momentous occasion.

Ever since Lucasfilm (or Disney, or whoever you want to call it) decided to continue the iconic space opera, Hannah and I have been keeping tabs on all the updates, leaks, and releases of the upcoming films. So, since the release of The Last Jedi coincided with Hannah’s birthday, it became the perfect birthday gift.

But, to make sure we had all the story up to date when we watched The Last Jedi, we went back and watched the The Force Awakens first. And while watching The Force Awakens, a very unusual conversation popped up around one particular scene.

In the movie, there’s a moment where C-3PO (a gold, very proper, humanoid robot, if you’re unfamiliar with the films) pops out of a spaceship, greets everyone and says, “you probably don’t recognize me because of the red arm.” Camera pans to a full body shot of the droid, showing his usual golden arm replaced with a bright red one. Cue running gag for the remainder of the film.

Seeing this, Hannah says, “Huh, I guess that makes sense...you know, when a car gets damaged, sometimes the coloUr of the part doesn’t match. It’s probably the same for droids.”

To which I responded, “Yeah, kind of like when 3PO had a silver leg in the first Star Wars trilogy.”

Instead of getting an “Oh right,” or “Yeah, I remember,” all I got back from Hannah was a confused stare.

“What are you talking about? He’s always been gold. What silver leg?”

The Force Awakens gets paused. Multiple Google image searches ensue.

Eventually Hannah concedes that the silver leg did indeed happen, but she’s sure that she remembers it differently.

Alas, Hannah is another victim of…(cue dramatic music)

The Mandela Effect.

Ok, so what is the Mandela Effect? Well, to put it simply, it’s a memory you possess about something that you are absolutely sure is true, but isn’t. But, it’s not just you. Hundreds - or even thousands - of people remember the exact same thing.

For example, a very large amount of people grew up reading The Berenstein Bears: a wonderfully innocent, wholesome series of children’s books that taught valuable morals through the family life of anthropomorphic cartoon bears.

Except that’s wrong. It’s the Berenstain Bears.

Many, many people are convinced that the names of these bears are, and always have been Berenstein (and, coincedentally, one of those people is Hannah).

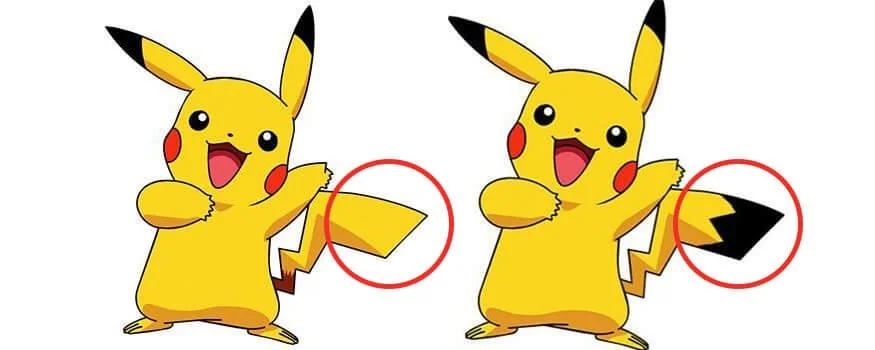

Countless examples of this strange phenomena exist. Many people remember Pikachu’s tail having a black tip (it doesn’t). Or growing up watching the classic children’s cartoon The Looney Toons (actually spelled Tunes). Or that Carrie, Charlotte, Miranda, and Samantha all had wacky adventures in Sex in the City (but it was actually Sex and the City). Or that the air-freshening spray Febreeze is spelled with three E’s (It’s not; it’s Febreze). Or that the comedian Sinbad starred in a movie in the 90’s called Shazaam where he played a genie (he didn’t).

Or probably the most notable example: the reason why this curious phenomena is actually called the Mandela effect...Nelson Mandela himself. Nelson Mandela served twenty-seven years in prison from 1962 to 1990. However, a very large amount of people are sure he died in prison sometime during the 1980’s.

But why? Why does this happen? Why do so many people collectively share these false memories? Well, there’s a couple explanations.

The first comes from, of all places, a cat in a box. Schrodinger’s cat, to be exact.

Schrodinger’s Cat is quantum physics thought experiment. It’s initial use was to help conceptualize something called the Copenhagen Interpretation: basically, very small things (like electrons, for example) don’t actually have any properties until they are measured or observed. Schrodinger’s Cat gives us a real-world hypothetical analogy.

Schrodinger has a box. In the box is a cat, and a mechanism that has a 50/50 chance of killing said cat. But, until you open the box, you have no idea whether or not the cat is alive or dead. So, until you observe the cat, it exists in both states; it’s living and dead at the same time.

By opening the box, you force the fabric of reality to choose an outcome. So, you wind up with either a very happy, fluffy new pet, or a dead one. But what happens to the other outcome?

Some believe in a Multiverse Theory. This theory says that the cat both lives and dies. When you open the box, you experience one reality (say the one where the cat lives). But, at that point, reality splits. A whole new branch of reality is created, where the cat is dead, you’re sad, and you curse reading this blog in the first place. But, because you’re living in this reality, you can never experience that other reality. And, as the theory goes, any decision with multiple outcomes creates a new universe, leading to an infinite amount of possibilities, combinations, histories, and experiences.

To some, the Mandela Effect is a “break” in these untouchable multiverses. All of these collective false memories are remnants of reality “skipping to the next track” where what we’re mis-remembering was what was actually real.

Another explanation is that a group of people remembering a particular Mandela Effect phenomena are remnants of time travellers coming back and fixing the past. So, there’s that.

Admittedly, these explanations of the Mandela Effect are a bit sci-fi. A lot of theories and explanations of quantum physics don’t scale up when you get past things the size of an atom. And, there has been no science or evidence to support time travel. And while it’s really cool to imagine what alternate realities would be like or being able to travel to the past to fix wrongs, I think the more realistic (and honestly, to me, the more interesting) explanation has to do with the three-pound lump of gooey flesh in your skull.

As I’ve mentioned before, our brains aren’t perfect. They move our bodies when we’re not aware, they make us slaves to social influence, they make us see things that aren’t there, and in this case, they remember things that never happened. In this article, I’ve called examples of the Mandela Effect false memories. Which, in the world of psychology, is a real, studiable thing.

In a nutshell, sometimes memories are fallible. And in the case of the Mandela Effect, there’s a few possible explanations as to why this happens. The first is that when it comes to memories, they’re coded in the brain through a branching path of neurons. Basically, when your brain creates a memory, the memory is stored as a “packet” of information. But, sometimes, connections get crossed when memories are remembered, which can create confusion. For example, The genie-themed movie Shazaam with Sinbad doesn’t exist, but Shaquille O’Neal starred in a genie-themed movie called Kazaam in the 90’s. While the general details between the two facts are similar enough to create a miscommunication in the brain when trying to remember the details. When someone finds evidence of the misinformation, it reinforces the false memory until the brain is sure it’s fact.

Another explanation is that when people are faced with unfamiliar, odd or strange facts, they will sometimes fill in the gaps with easier-to-understand (albeit incorrect) information (or in other cases, omit information entirely). One study asked participants to draw the face of a clock from memory: now this particular clock used Roman numerals to indicate the numbers on the clock face. And, because it made for a more pleasant aesthetic, the makers of the clock opted for a “IIII” instead of a “IV” to indicate the number four. But, because of familiarity, the participants in the study used “IV” in their recreations of the clock. A similar study asked people to describe what they remember about a psychologist’s office...and while most of them remembered the desk, the books, the shelves, and the chairs...almost none of them remembered the out-of-place picnic basket in the middle of the room.

Finally, a lot of the Mandela Effect false memories are simply because of a fact going against otherwise correct rules or expectations. Most people remember that the delicious chocolate bar KitKat has a hyphen in the middle (“Kit-Kat”) when it doesn’t. While the correct version of the chocolate bar name doesn’t have a hyphen, English grammar rules says that it should. So, we accept that as real, and the misremembering ensues. Or, you expect something to be true, so you remember it as such. Since ninety percent of C-3PO is gold, it makes sense that his (actual) silver leg is, too.

All of these explanations are reinforced when we run up against someone who misremembers something in a similar way. Our already-fallible brains are reinforced by the faults in someone else’s. And, because we all operate with similar machinery and within similar rules, it makes sense that we all misremember things in the same general way.

But why do I care? Because it’s my job.

As a magician, there’s a lot of times where I rely on you misremembering something. In fact, in some cases, I engineer it to be that way. Did I really not touch the deck of cards? Did I really do things in the order I said I did? A good magician will take advantage of the fact that the human brain isn’t perfect. In fact, their career depends on it. And mistaken memory is a powerful tool to pulling off miracles.